Exploring Society: Innovations and tech advancements impact on society.

Outline:

– Connectivity and civic life: infrastructure, inclusion, and resilience

– Automation and labor: productivity, displacement, and new roles

– Data and trust: privacy, governance, and incentives

– Learning and citizenship: skills, literacy, and institutions

– Conclusion: practical steps for people, organizations, and policymakers

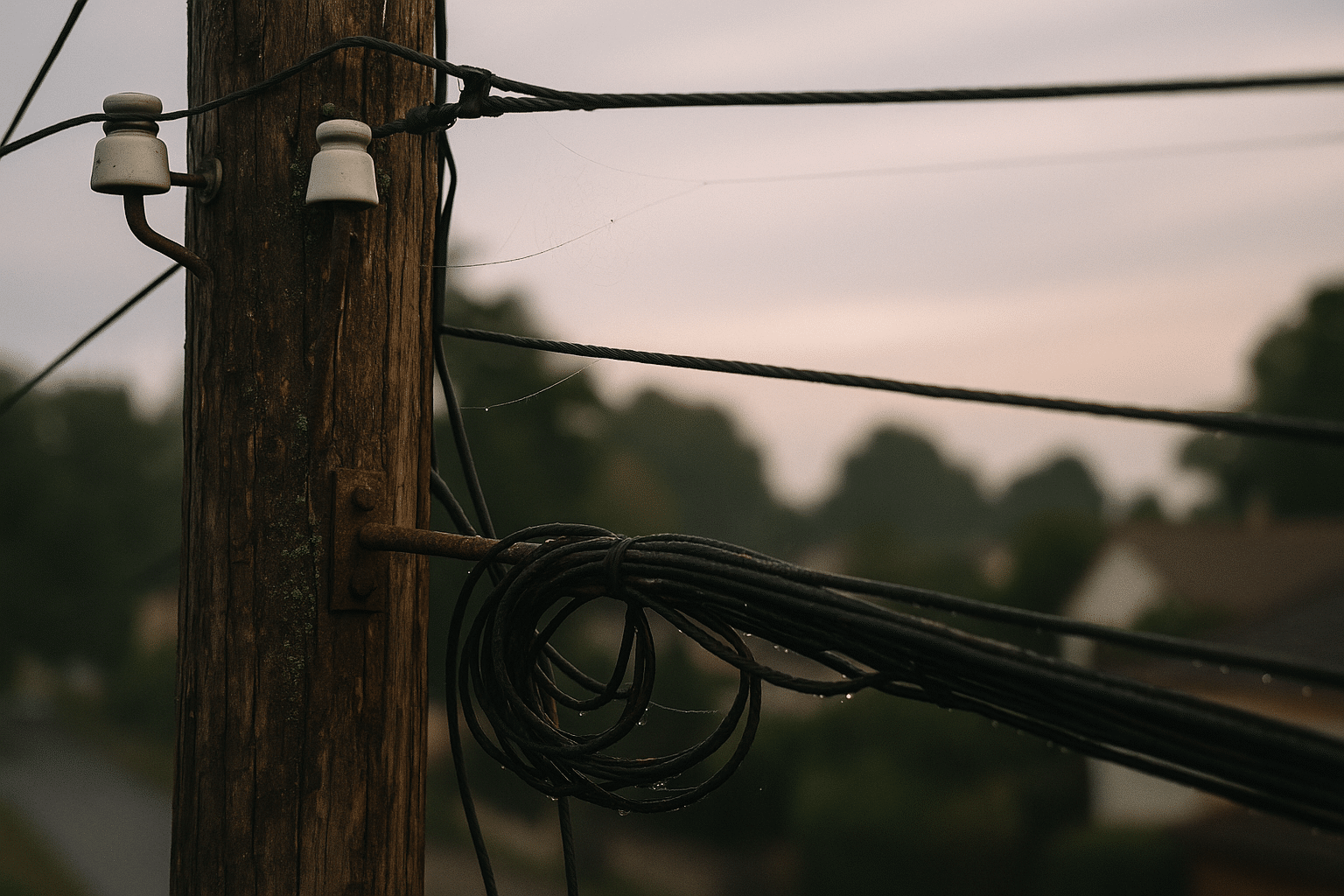

The Web of Connectivity: Infrastructure, Inclusion, and Resilience

Walk any city block or country lane and you are traveling alongside invisible threads of code and light. Connectivity no longer just moves entertainment; it moves identity documents, job applications, health appointments, and disaster alerts. Over the last decade, median mobile and home connection speeds have multiplied, while households in many regions now maintain more than one active subscription per person. That expansion carries uneven edges. Dense areas often enjoy fiber-fed abundance, while remote communities juggle higher costs, unreliable backhaul, and weather-sensitive wireless. The stakes are civic, not merely technical: access determines who participates, who benefits, and who waits.

Compare the common access modes and you see distinct trade-offs that matter for daily life and public planning. Fiber emphasizes capacity and reliability but requires trenching and long payback periods. Cable and hybrid networks can offer high speeds with wider availability, yet performance may fluctuate at peak times. Fixed wireless becomes a lifeline where terrain blocks digging, although signal quality can fade with foliage, rain, or interference. Satellite expands coverage to the edges, trading latency and data caps against reach. The right mix is rarely a single technology; it is a portfolio tailored to geography and budget.

Consider the benefits citizens actually feel:

– Access to services: applying for benefits, scheduling telehealth, and joining town meetings without travel time.

– Economic participation: remote work, local e-commerce, and digital payments that keep money circulating locally.

– Crisis response: early warnings, resource maps, and coordination that reduce confusion during storms and fires.

None of these arrive automatically. Affordability programs, community Wi‑Fi, and shared devices in public libraries remain vital bridges. Reliability also matters: a study of outage reports in multiple regions shows that a handful of short disruptions can erase the value of higher headline speeds when timing is unfortunate—during exams, job interviews, or emergency alerts.

Resilience is the quiet hero of connectivity. Communities are experimenting with mesh networks that reroute traffic around a damaged node, local caching that keeps essential information available during backhaul failures, and microgrids that power cell sites through multi-hour outages. Responsible planning layers redundancy: two routes to the internet, diversified vendors, battery and solar backups for critical hubs, and clear communication during incidents. As infrastructure modernizes, the social contract should modernize too: plain disclosures of performance, transparent maintenance schedules, and service levels aligned with civic needs, not just weekend streaming. When access is reliable, inclusion follows; when it is fragile, mistrust grows.

Automation and Labor Markets: Productivity, Disruption, and New Roles

Automation is not a single machine; it is a continuum of tools that shift how tasks are performed. From document classification to warehouse routing to field sensors that guide irrigation, software and machines move routine work from people to processes. Historical data across multiple sectors suggests a common pattern: output rises, tasks change, and jobs reconfigure rather than vanish wholesale. The transition, however, can be jarring for individuals and small firms, especially where training budgets are thin and time to learn is scarce. The question is not whether tasks will change, but how to pace the shift so that paychecks and dignity keep pace with the promise of efficiency.

A useful lens divides work into three buckets:

– Routine manual: predictable physical activities in stable settings.

– Routine cognitive: structured information tasks with clear rules.

– Non-routine: judgment, empathy, creativity, and complex coordination.

Automation advances fastest in the routine categories. Yet even in those domains, most deployments are partial. For example, scheduling tools allocate shifts, while supervisors still negotiate conflicts and handle exceptions; agricultural sensors flag anomalies, while farmers interpret context from soil to sky. In many pilots, teams report time savings in the 10–30% range for specific tasks, which translates into either higher throughput or room for better service, rather than immediate job cuts.

The design of adoption matters as much as the technology. Capital-heavy robots that require reconfiguring entire workflows can lock organizations into inflexible choices, while modular tools that augment workers allow incremental learning and faster iteration. Small and mid-sized enterprises often gain more from low-cost automation—templates, checklists, and decision-support—than from large, bespoke systems. To keep opportunity broad, training needs to move closer to the shop floor and the back office: short, job-embedded modules; peer coaching; and practice with real data rather than classroom hypotheticals.

For workers eyeing the horizon, three durable capabilities stand out: process literacy (seeing how work flows end-to-end), data sensemaking (asking better questions of information), and collaborative problem solving (linking human strengths with machine outputs). For managers, responsible adoption means publishing the goals of automation before rollout, measuring not only cost per unit but also safety, error rates, and customer satisfaction, and setting aside time for feedback cycles. For communities, the policy play is practical: portable learning records, stipends that support upskilling between gigs, and hiring signals that reward skills, not just credentials. With these guardrails, automation becomes a ladder, not a trapdoor.

Data, Privacy, and Trust: Guardrails for Everyday Technology

Data powers most of the conveniences people enjoy, from route suggestions to smarter thermostats. It also powers the discomfort many feel when ads seem to know too much or when a service buries consent under layers of jargon. Trust in digital systems is built less on promises and more on predictable behavior: collect only what is needed, protect it well, and explain in plain terms why it is collected. People do not expect perfection, but they do expect honesty and recourse. Organizations that align incentives with user outcomes tend to retain loyalty when inevitable mistakes occur.

Consider two design paths. In a centralized model, information is aggregated in a single repository that simplifies analytics but increases breach impact. In a distributed model, data stays closer to the edge—on devices or local nodes—reducing systemic risk but demanding stronger coordination and on-device processing. Privacy-respecting techniques now make meaningful analysis possible without exposing raw records. Examples include adding statistical noise to obscure individual contributions, training models across devices without transferring personal data, and summarizing sensitive inputs before transmission. None of these erase risk, yet they shift the balance toward utility with restraint.

Practical steps help move from principle to practice:

– Minimize by default: if a feature does not require location, do not request it.

– Explain purpose: state in a sentence how the data improves a service and for whom.

– Limit retention: set clear deletion timelines and honor them automatically.

– Verify vendors: ensure partners follow equivalent standards, not weaker ones.

– Offer real control: consent that is readable, revocable, and remembered.

For individuals, small habits compound: reviewing permissions quarterly, using passphrases, enabling multi-factor logins, and separating personal from financial email addresses can dramatically reduce exposure.

Trust is also institutional. Public bodies and companies can publish incident postmortems, create independent oversight boards with access to logs, and run red-team exercises that probe systems before attackers do. When things go wrong—and they will—transparent timelines and fair remediation matter. People remember how organizations behave under stress. Making security updates routine, rewarding responsible disclosure, and connecting performance metrics to privacy outcomes signal that data stewardship is not a side task; it is part of quality. The goal is not secrecy; it is consentful, comprehensible data use that earns the right to operate.

Learning and Civic Competence in a Tech-Driven Era

Knowledge used to arrive in thick textbooks and scheduled lectures. Today it flows in short videos, interactive labs, chat interfaces, and community forums. That abundance is a gift—and a maze. The skills that matter most are not only technical but also meta-cognitive: how to frame a problem, evaluate sources, and iterate toward a workable solution. Lifelong learning is no longer aspirational language on a poster; it is a practical survival skill for citizens and organizations navigating rapid change.

Different learning modes serve different goals. Synchronous sessions create accountability and live feedback, which helps with complex or emotionally demanding topics. Asynchronous modules reduce friction for busy schedules and enable spaced repetition, a proven approach to retention. Project-based learning ties knowledge to action: a small team builds a dashboard for a local nonprofit; a student compares energy use in two buildings; a neighborhood group maps safe routes to school. These projects provide context that generalizes beyond the tool of the moment.

Three literacies deserve special focus:

– Information literacy: checking claims against multiple sources, noting incentives, and identifying common fallacies.

– Data literacy: reading charts, understanding uncertainty, and separating noise from signal.

– Digital well-being: attention hygiene, mindful notifications, and boundaries that preserve rest and creativity.

Accessible design multiplies impact. Offline-first materials help learners with inconsistent connections. Subtitles, transcripts, and alternative formats assist everyone, not just those with disabilities. Community spaces—libraries, makers’ workshops, and local classrooms—turn learning into a social anchor where peers support each other’s progress.

Credentials still matter in hiring, but the signal is shifting toward demonstrable skills. Portfolios that show before-and-after artifacts, reflective write-ups explaining trade-offs, and code or data notebooks that reproduce results carry weight. For educators and managers, the challenge is to assess not only accuracy but reasoning: how students and employees arrived at an answer, what they tried when the first approach failed, and how they incorporated feedback. For learners, a sustainable routine beats a burst of intensity: short daily practice, targeted curiosity, and periodic reflection. Over time, these habits create confident, adaptable citizens able to hold their own in civic debates shaped by technology.

Conclusion: A Practical Playbook for Citizens, Organizations, and Policymakers

Technology’s influence on society is not destiny; it is the result of millions of small choices that add up. To steer those choices, it helps to work on different time horizons. In the next 90 days, citizens can audit their privacy settings, back up critical files, and set aside an hour a week for a learning goal. Community groups can map local connectivity gaps and share outage experiences to inform negotiations with providers. Small businesses can document one key process and experiment with a modest automation tool that frees time for service quality.

Over the next 12 months, organizations can align incentives with responsible outcomes: performance reviews that reward data stewardship, budgets that include accessibility from the outset, and procurement checklists that evaluate interoperability, resilience, and privacy alongside price. Workforce plans can shift from one-off trainings to continuous learning with micro-projects tied to real work. Schools and libraries can partner to provide quiet study spaces, device lending, and mentorship circles that mix ages and backgrounds. Local governments can publish modernization roadmaps that explain not only what will be built but why and how residents can give input.

Looking two to three years out, coalitions can invest in shared infrastructure that no single actor can shoulder alone: neutral fiber backbones that support multiple providers, regional security operations that help small institutions respond to threats, and open-data portals with clear governance and safeguards. Periodic resilience drills—simulating outages, testing backup power at cell sites, or practicing manual fallbacks—turn abstract plans into muscle memory. Independent audits of algorithmic systems, coupled with public summaries, keep accountability real without revealing sensitive details.

Across all horizons, a few principles hold steady:

– Design for inclusion first; everyone benefits when the edges are served.

– Measure what matters; count reliability, safety, and satisfaction, not only cost.

– Communicate simply; trust grows when people understand trade-offs.

If citizens cultivate literacies, organizations adopt human-centered automation, and policymakers invest in reliable, affordable access, society can harness innovation without surrendering agency. The future is not about faster gadgets; it is about wiser systems—and the people ready to use them well.