Explore the world of swimming

Swimming sits at a rare crossroads: it is exercise, skill, and mindful practice in one. It is accessible to many body types and ages, scales from easy recovery to demanding intervals, and offers a soothing environment that can quiet a noisy day. In a world short on spare minutes, swimming rewards consistency with steady gains—stronger heart and lungs, smoother movement patterns, and a clearer head. This guide explores how strokes work, why water-based training supports health, how to plan sessions safely, and which settings and gear can elevate your time in the pool or open water.

Outline of this article:

– Technique and biomechanics of the main strokes

– Health benefits and how the body adapts in water

– Training structure, skill progressions, and safety

– Gear, pools, and aquatic environments compared

– Conclusion with next steps for different swimmer types

Technique and Biomechanics: How Strokes Work

Efficient swimming is less about brute force and more about reducing drag while creating focused propulsion. Water is dense; every misaligned hand or lifted head adds resistance. Think of your body as a long vessel: align the head, hips, and heels to minimize frontal area and keep the core engaged to stabilize rotation. Across strokes, propulsion comes from a coordinated pull, a streamlined body line, and a kick that balances rather than overpowers.

Front crawl (often called freestyle) is the most economical and typically the fastest stroke. The keys include:

– A relaxed, rhythmic flutter kick driven from the hips

– High-elbow catch to press water backward rather than downward

– Neutral head with side breathing timed to body roll

– Streamlined entry, fingertips leading, to avoid bubbles on the hand

Backstroke mirrors crawl with an upward-facing body position. It rewards steady rotation around the spine, a flat hip line, and a continuous arm recovery that clears the water without flailing. Breaststroke, by contrast, trades speed for timing and glide. The pull is a heart-shaped sweep that sets up a streamlined spear, while the whip kick provides a compact burst of thrust. Butterfly is a rhythm game: a powerful chest-driven undulation, simultaneous arm pulls, and a two-beat dolphin kick per cycle to keep momentum.

From a physics perspective, swimmers manage three main types of drag: form drag (shape-related), wave drag (surface waves), and skin friction. Good technique reduces form drag by keeping the body long and narrow; well-timed breathing lowers wave drag; and smooth entries reduce turbulence, which lessens skin friction effects. Practical cues help:

– Exhale steadily in the water; sip air quickly when you turn to breathe

– Keep the lead arm extended during crawl breathing to maintain balance

– Press the chest slightly in butterfly to set the body’s natural wave

– In breaststroke, finish the kick before beginning the next pull to protect momentum

In terms of effort, lap swimming spans roughly 6–10 METs depending on stroke and intensity, placing it from moderate to vigorous activity for many adults. That range means you can use technique to scale the work: streamline and long strokes for economy, higher cadence sets for speed, and drill sets to retool mechanics without overtaxing the system. The water is honest feedback—quiet hands, steady rotation, and relaxed breathing usually lead to faster times without extra strain.

Health Benefits and Physiology: Why the Water Works

Water changes the rules of movement. Buoyancy reduces joint loading compared with land exercises, which helps many people train consistently even with sore backs, knees, or hips. At the same time, the resistance of water challenges the cardiovascular and muscular systems through a full, controlled range of motion. The result is a workout that is both protective and potent—an appealing combination for long-term fitness.

Cardiorespiratory effects are well-documented: regular swimming improves stroke volume (the amount of blood pumped per beat) and can increase maximal oxygen uptake with structured interval work. Because water pressure subtly aids venous return, many swimmers note lower perceived exertion at a given heart rate versus land training. For everyday outcomes, that translates into easier stair climbs, better endurance for hikes or cycling, and steadier energy across the week.

Calorie expenditure varies with body size, pace, and stroke. Typical estimates for a 30-minute session range from roughly 180–300 calories at an easy-to-moderate effort to 300–500 calories at a strong pace, with butterfly and vigorous crawl trending higher due to larger muscle recruitment and drag. Beyond calorie counts, muscular balance stands out. Swimming trains the back, shoulders, core, and hips in harmony, while the kick activates glutes and quads without impact. Adding simple land-based resistance (like squats, rows, and presses) can complement pool work to support bone health, as swimming itself is not weight-bearing.

Mental benefits are notable. Many swimmers report reduced stress and improved mood after sessions, aided by rhythmic breathing and the “envelope” effect of immersion. Cool or temperate water can encourage a parasympathetic response post-workout, which supports recovery and sleep. Practical advantages include:

– Low joint stress enables higher training frequency with less soreness

– Temperature control reduces overheating common in summer workouts

– The environment curbs distraction, encouraging mindful focus

– Skills scale from gentle therapy to vigorous conditioning

For older adults or beginners, aquatic training can be a gateway to consistent movement; for experienced athletes, it can be a high-yield cross-training tool that spares joints while pushing the aerobic engine. The versatility is the point: the same lane can host recovery one day and quality speed work the next.

Training Structure, Skill Progression, and Safety

A thoughtful plan turns random laps into steady progress. Start with a purpose for each session—technique, endurance, speed, or recovery—and build a simple structure around it: warm-up, drill or skill block, main set, and cool-down. Even two sessions per week can move the needle if they are focused and repeatable.

Consider three sample paths:

– Beginner: 2–3 sessions/week. Warm up with 5–10 minutes easy, add 6–8 short drill repeats (25–50 meters) focusing on balance and breathing, then a main set like 6×50 meters at a relaxed pace with 20–30 seconds rest. Finish with easy backstroke to loosen shoulders.

– Intermediate: 3–4 sessions/week. One technique day with drills (catch-up, fingertip drag, sculling), one aerobic day (e.g., 3×400 meters steady), one quality set day (e.g., 12×100 meters at moderate-hard with even splits), and optional skills day (kicking and pace work).

– Open water oriented: 2–4 sessions/week. Include long continuous swims to practice sighting every 6–10 strokes, and pool sets with buoy turns and variable pacing to mimic currents and chop.

Periodization helps distribute stress: spend several weeks building volume and technique, a block emphasizing pace and strength, then a short sharpening phase before an event or time trial. Land conditioning matters—planks, band external rotations, and rows support a healthy shoulder; calves and hamstrings work support ankle flexibility and a steady kick. Recovery basics count too:

– Aim for 7–9 hours of sleep to consolidate adaptations

– Refuel within an hour post-swim with a mix of protein and carbohydrates

– Schedule a lighter “deload” week every 4–6 weeks to avoid plateaus

Safety is non-negotiable. In pools, follow lane etiquette: pick a lane that matches your pace, circle swim when shared, leave a few seconds of gap, and avoid prolonged breath-holding games, which can be dangerous. In open water, plan route and exits, check weather, and swim with a visible buoy and a partner when possible. Learn to read currents: rip currents flow seaward and are escaped by swimming parallel to shore before angling back. Temperature adds complexity; acclimatize to cold gradually, limit exposure, and exit promptly if shivering or dexterity declines. A simple checklist—tell someone your plan, carry a bright cap, and know local hazards—turns adventure into a confident habit.

Gear, Pools, and Aquatic Environments

The right gear need not be elaborate, but a few items support comfort and skill work. Goggles that seal well protect the eyes and improve visibility; low-profile designs reduce drag for speed sessions, while larger lenses can feel calmer in open water. A cap streamlines hair and reduces drag. Suits should fit securely and allow full shoulder mobility. Training tools each have a purpose:

– Kickboard: isolates the legs for focused kick practice

– Pull buoy: lifts the hips to emphasize arm mechanics and body line

– Paddles: add surface area to the hand, highlighting catch quality and shoulder strength (use with care)

– Fins: improve ankle mobility, reinforce body position, and add speed for drill feel

– Snorkel: removes the timing of breathing so you can focus on alignment

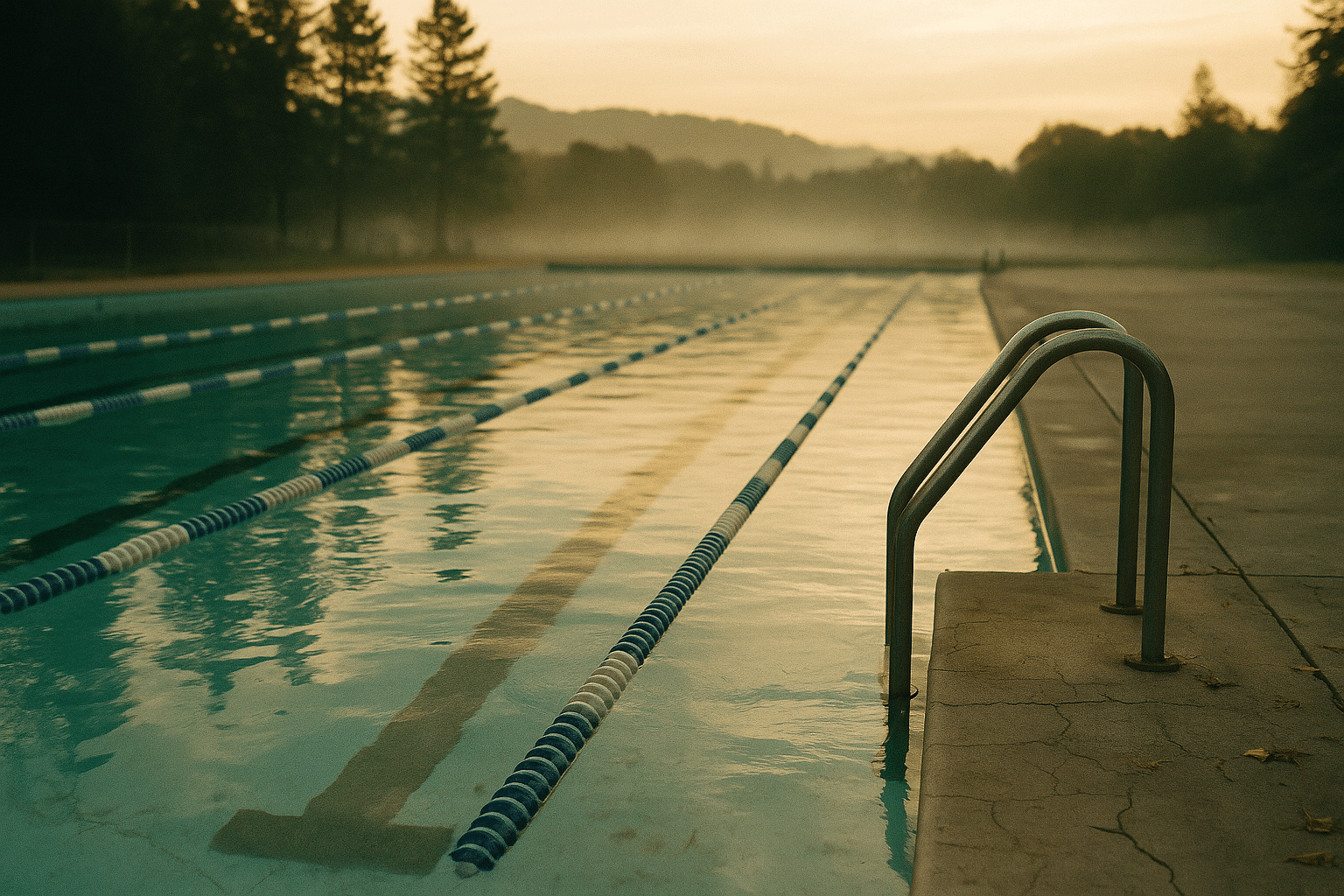

Pools vary. Short-course pools are commonly 25 meters or 25 yards and favor turns and skills; long-course pools are 50 meters and emphasize sustained pacing. Water temperature between roughly 26–28°C suits training, while recreational settings often sit a bit warmer. Lane lines reduce turbulence, gutters draw away waves, and well-designed pool decks minimize glare and slip risk. Water quality matters for comfort and health: balanced pH (around 7.2–7.8) and appropriate disinfectant levels help curb irritation and pathogens. A strong “chlorine” smell often indicates chloramines from organic matter—showering before you swim and rinsing gear afterward helps keep water fresh.

Open water introduces richness and responsibility. Lakes, rivers, and the sea offer changing textures—glass-calm mornings, wind-driven chop in the afternoon, and moody overcast days with low contrast. Check local advisories for water quality and hazards, and choose clear landmarks for sighting. Wetsuits can extend comfort in cooler temperatures and add buoyancy, though they slightly alter body position. A bright cap, reflective tow float, and awareness of boat traffic improve visibility. Environmental considerations are practical and respectful:

– Rinse and dry gear to prevent transporting invasive species

– Avoid applying lotions that wash off easily; choose water-resistant options applied well in advance

– Reuse bottles and minimize single-use plastics on deck or shore

– Shower before entering to reduce chemical by-products in pools

Ultimately, the environment you choose should match your goals: precise pacing and drills thrive in a pool; adventure, navigation skills, and variable pacing bloom in open water. Many swimmers blend both to enjoy structure on weekdays and exploration on weekends.

Conclusion: Your Next Length

If you are starting out, keep it simple: two or three short sessions a week, a few basic drills, and patient attention to breathing. Measure progress by comfort and control, not just speed. If you are returning, layer structure—alternate technique emphasis with aerobic sets, and add light strength training to support shoulders and hips. If you already train regularly, use periodization to sharpen pacing and sprinkle in open-water skills or mixed-stroke work to round out your engine.

Across levels, the same principles apply. Reduce drag before adding force; align the body before chasing turnover; and build consistency before intensity. Safety habits make confidence possible, while modest gear choices improve feedback and feel. Consider setting a small goal—a continuous 500 meters, a local timed session, or a friendly open-water loop—and map four to six weeks of sessions to get there. The water rewards honest effort: quiet strokes, steady breathing, and curiosity about small improvements. Slip into the lane or step to the shore, and let today’s length be the start of a new, sustainable rhythm.