Exploring Society: Innovations and tech advancements impact on society.

Outline

– Connectivity and the social fabric

– Work, automation, and human skills

– Health and wellbeing in a sensor-rich era

– Cities, environment, and infrastructure

– A practical roadmap for citizens and leaders

Introduction

Innovation is not an abstract idea humming in distant labs; it’s a daily companion shaping how families communicate, how neighbors organize, and how institutions serve the public. As devices, networks, and data systems scale, their influence reaches classrooms, clinics, offices, farms, and streets. Understanding this wide-angle impact helps communities seize clear benefits—greater access, higher productivity, cleaner air—while managing real risks such as exclusion, privacy loss, and fragile trust. The pages that follow pair grounded evidence with practical steps so readers can navigate change with purpose.

Connectivity and the Social Fabric

More than half of humanity is now online, and mobile subscriptions number in the billions, with many individuals maintaining multiple lines for work and home. This connectivity has reshaped social capital: families maintain dispersed ties, neighborhood groups rally faster after storms, and local entrepreneurs find customers beyond their postal codes. Yet the same channels amplify rumors, expose private moments to public scrutiny, and create echo chambers that reward outrage. The social web is a mirror and a megaphone; what we bring to it—curiosity or contempt—sets the tone for what comes back.

Evidence from large household surveys shows that digital communication can sustain weak ties, which are vital for job leads and civic opportunities. Studies of crisis response find that community forums and messaging groups accelerate coordination, reducing the time it takes to match volunteers with needs. But the gains are uneven: rural districts with poor coverage and households without affordable data plans rely on slower, costlier pathways to information. When access gaps persist, new services unintentionally deepen old divides.

Three lenses help communities assess impact:

– Traffic: How many people can reach essential information and services within minutes, regardless of income or location?

– Trust: Do residents understand how content is ranked, and can they verify sources easily?

– Time: Are tools reducing coordination time for schools, clinics, and local associations, or merely adding notification noise?

Practical steps are clear. Municipal networks and shared access hubs can lower costs where private investment lags. Public institutions can publish critical updates in low-bandwidth formats and multiple languages. Community-led “digital neighbor” programs, where trained volunteers help others set up devices and evaluate sources, have increased uptake of e-services in several regions without requiring large budgets. Connectivity is not an end in itself; it is the plumbing for community life. Making it reliable, inclusive, and comprehensible turns pipes into pathways for opportunity.

Work, Automation, and the Value of Human Skills

Across sectors—from logistics and agriculture to finance and hospitality—software and machines now perform tasks that once demanded routine human effort. Multiple labor-market studies estimate that a significant share of job tasks, often between one-fifth and two-fifths, can be partially automated with current tools. That does not translate one-to-one into job losses; rather, roles are re-bundled. Workers spend less time on repetitive input or inspection and more time on oversight, problem-solving, and interaction with clients or citizens. Still, transitions are disruptive when firms adopt tools faster than people can retrain.

Productivity data often show a lag: new systems arrive, learning curves absorb time, then output climbs. This “transition tax” can last months or years, particularly in small organizations without dedicated training budgets. Meanwhile, new occupations emerge in data stewardship, human-centered design, and maintenance of automated systems. Historically, technology has both displaced and created roles; the direction communities experience depends on how quickly education providers, employers, and public agencies align around reskilling.

Workers and managers can take tangible steps:

– Map tasks, not jobs: identify activities ripe for automation and those where human judgment, empathy, and ethics are central.

– Build learning time into schedules: micro-courses and peer coaching embedded in weekly routines raise adoption and morale.

– Measure outcomes, not installations: track error rates, service response times, and safety incidents to ensure tools solve problems.

Policy matters too. Portable training accounts, short accredited courses, and recognition of prior learning help mid-career workers switch tracks without leaving the labor force. Local partnerships that pair employers with education providers can publish skills roadmaps so students see clear paths into good work. Transparency about performance metrics reduces fear: when people know automation targets specific bottlenecks—say, invoice matching or crop monitoring—they are more willing to contribute expertise that makes systems resilient. The enduring edge remains human: situational awareness, values-driven decisions, and the creative leaps that connect dots machines do not see.

Health and Wellbeing in a Sensor-Rich Era

Health services have embraced remote consultations, home monitoring, and triage algorithms, particularly during periods when travel or in-person visits were constrained. In many regions, remote appointments multiplied several-fold within a single year, and patient satisfaction for routine follow-ups often matched in-clinic benchmarks. For chronic conditions such as hypertension and diabetes, connected devices can supply frequent readings, allowing clinicians to adjust plans before problems escalate. Early detection and adherence nudges are meaningful when they prevent emergency care or long hospital stays.

But technology is not a cure-all. Not all symptoms are visible on a screen; touch, smell, and in-person observation still matter. Some apps deliver promising results in mental health, especially programs rooted in evidence-based methods, yet they require sustained engagement that is hard to maintain. Data privacy concerns are legitimate: health histories are sensitive, and breaches can cause lasting harm. Ethics reviews, data minimization, and transparent consent flows are essential to maintain trust.

A balanced approach helps:

– Match the tool to the task: remote visits for stable follow-ups; in-person for complex diagnosis or physical exams.

– Prioritize accessibility: low-bandwidth options, captioning, and clear interfaces reduce barriers for older adults and people with disabilities.

– Close the feedback loop: patients should see how their data improves care plans, reinforcing motivation to participate.

Community health outcomes also depend on the basics: clean air and water, safe housing, nutritious food, and time for rest. Environmental sensors can identify pollution hotspots; open dashboards can inform targeted interventions like tree planting or traffic rerouting. When civic groups, clinics, and local agencies share goals—reducing asthma incidents, cutting wait times, increasing vaccination coverage—technology becomes a tool for coordination rather than an end in itself. The north star remains wellbeing, measured not just by devices deployed but by lives improved.

Cities, Environment, and Infrastructure

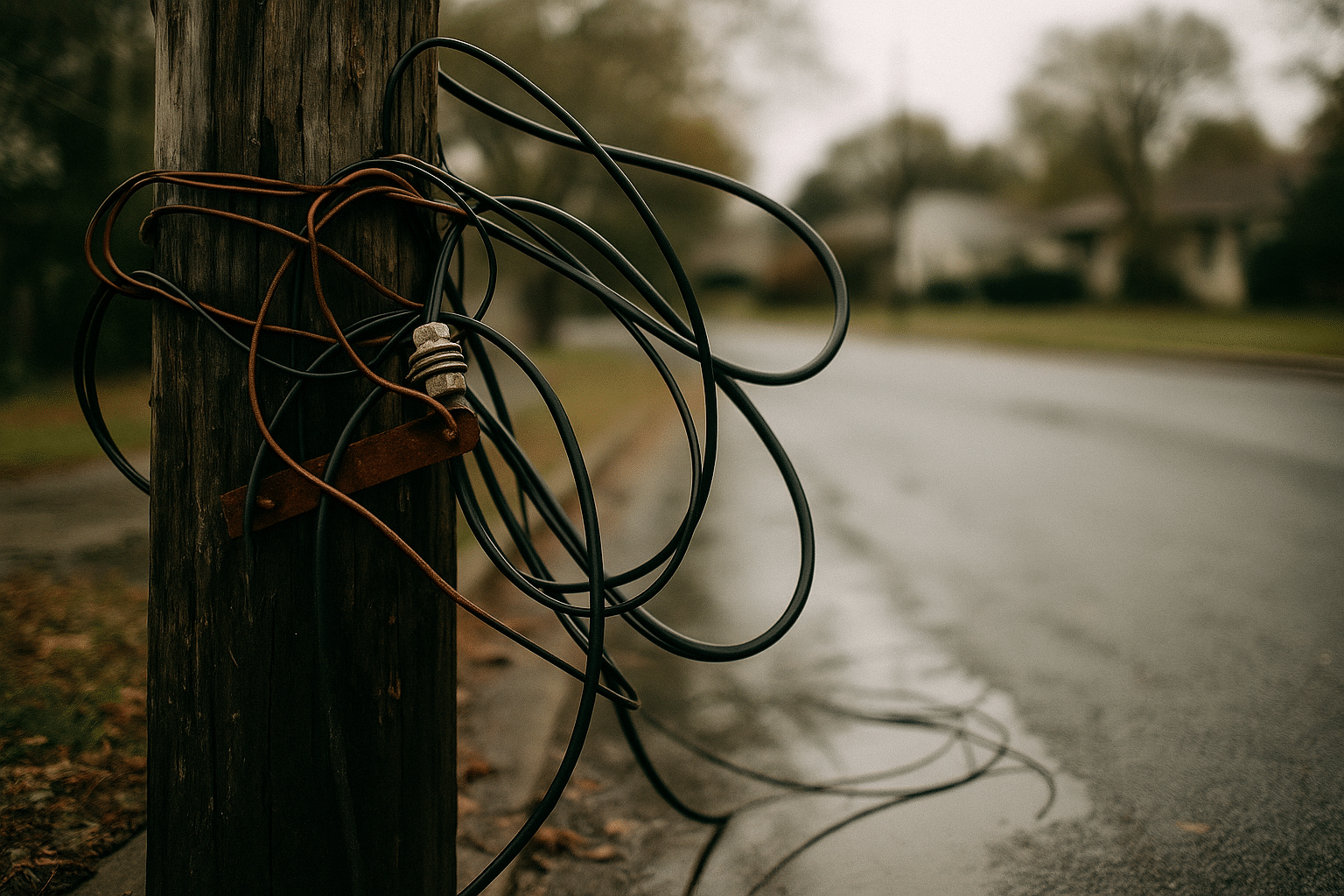

Urban life is a dance of infrastructure: power grids, water pipes, roads, buildings, and waste systems working—or failing—together. Buildings account for a large share of energy use in many economies, often near two-fifths when heating, cooling, and lighting are included. Transport contributes roughly a quarter of energy-related emissions worldwide. Smart meters, leak detection, and synchronized traffic signals can trim waste at meaningful scales, sometimes cutting losses in double-digit percentages. These gains reduce bills as well as pollution, making them attractive beyond environmental circles.

Real-world examples abound. Water utilities using continuous pressure monitoring have identified invisible leaks and prioritized repairs, saving millions of liters. Transit agencies with adaptive signal timing move more buses through congested corridors without expanding asphalt. Building operators deploying occupancy-based ventilation reduce energy use while maintaining comfort. Yet each improvement carries trade-offs: more sensors mean more data to secure; more connectivity expands the attack surface for malicious actors; and poorly governed surveillance can chill public life.

Environmental costs require attention, too. The world generates tens of millions of metric tons of electronic waste annually, and recovery rates remain modest. Extending device lifespans, standardizing components, and designing for repair can bend this curve. Cities can include circularity in procurement—awarding points for durability, modularity, and recycled materials. Community repair events, supported by libraries or schools, turn sustainability into a social ritual.

Guiding questions help keep projects humane and effective:

– Will this system reduce emissions per resident without increasing surveillance beyond necessity?

– Can residents understand, contest, or correct data that affects them?

– What is the maintenance plan, including spare parts and staff training, for five and ten years out?

When technology meets thoughtful governance, infrastructure becomes both smarter and kinder: lights brighten only where needed, buses arrive reliably, water flows without waste, and public spaces invite people to linger. The point is not to wire the city for novelty but to align tools with the timeless goals of safety, dignity, and shared prosperity.

A Practical Roadmap for Citizens and Leaders

Change feels abstract until it taps your shoulder: a new login for school notices, a chatbot at the clinic, a software update that rearranges your tools. Turning unease into agency starts with clarity about roles. Individuals, organizations, and public agencies each hold levers that shape whether innovations widen or narrow opportunity. This section offers actionable steps designed for everyday readers—parents, students, workers, caregivers, entrepreneurs, and public servants—who want progress without empty promises.

For individuals:

– Practice data hygiene: review privacy settings quarterly, rotate passwords, and limit permissions to what a service truly needs.

– Build a learning habit: set aside one hour a week to explore a skill—spreadsheets, data visualization, or community mapping—that strengthens your voice.

– Participate locally: join a school tech committee, a neighborhood safety audit, or a library class; proximity sharpens priorities.

For organizations:

– Start with a problem statement, not a tool wishlist. Define the outcome you seek—fewer errors, faster service—then test simple solutions first.

– Budget for adoption: training, process redesign, and support are part of the cost, not optional extras.

– Measure what matters: response times, user satisfaction, inclusion rates, and emissions intensity reveal real progress.

For public agencies:

– Codify transparency: publish plain-language summaries of algorithms that affect access to services, along with avenues for appeal.

– Protect the floor: ensure baseline access through public Wi‑Fi zones, device lending, and digital help desks, especially for newcomers and older adults.

– Plan for resilience: require offline fallbacks for critical services and invest in cybersecurity drills with community partners.

Finally, keep a humane compass. Ask whether a change preserves time for care work, supports local creativity, and strengthens trust between institutions and residents. Narratives matter: celebrate not just new deployments but the patient work of maintenance and repair. Society advances when innovations amplify human strengths—judgment, empathy, craftsmanship—and reduce drudgery without erasing dignity. With shared intent and steady iteration, communities can turn fast-moving technology into durable public value.